Indian Muscle

Around 40% of indians are vegetarian which makes the bodybuilding diet harder than normal. On average they consume 3000 calories per day

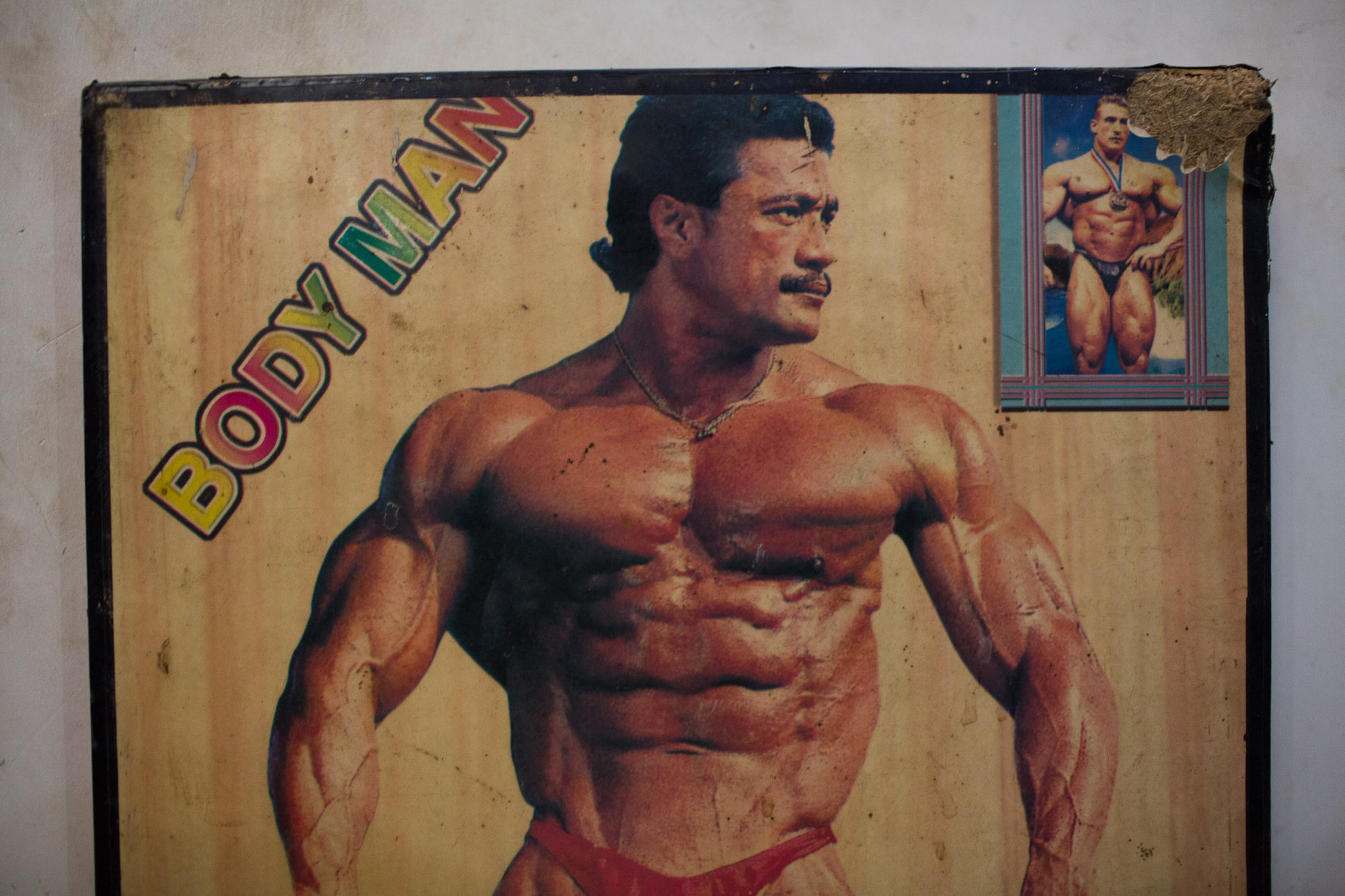

It is 6.30pm and the temperature hits 40 degrees, a typically hot spring day in northern India. Our photojournalist, Anders Birger, is visiting Keep Fit Health Club, a small gym haven for weightlifting locals, set in the basement of a guest house in Mathura, a small town in Uttar Pradesh. Drops of sweat glimmer in fluorescent light. Whirring sounds seep in from a ceiling fan. Posters with figures of famous bodybuilders from all over the world are spread over the walls and a group of men are gathered around, comparing weight lifts.

Our team of trained photojournalists see more than the casual observer. For us a gym is never just a gym. Immersed beneath the surface of the image, we discover centuries-long rituals interplaying with a sense of community and a desire for belonging. Layers of meaning attract and collide.

To understand the underlying traditions and drivers of bodybuilding, it’s worth going back to its roots. The practice was perfected by Ancient Greeks to help them improve their performance for olympic competitions at times of peace, and as fit-for-purpose soldiers in war times.

Yet it was in 11th century India that weight lifting as we know it first arrived on the scene. Indians would be the first civilization in history to build their bodies for the sole purpose of aesthetics. They used Nals, primitive dumb bell weights carved from stone, to shape their bodies. By the 16th century, weightlifting had become a national pastime in India, with weightlifting gyms being commonplace.

British Rule in India started a period of decline in Physical Culture and general health amongst the Indian population. In 1905, there was a revival of interest, driven by Eugen Sandow, the pioneer of modern weightlifting practices, and his highly successful visit to India. Thousands gathered around him with admiration, as if quenching their thirst for a once lost cultural identity.

It is believed that Krishna, the Hindu ‘God of Attraction’ normally represented as a young virile boy, was born in Mathura. Pilgrims visit the town and his temple all year. They pass in front of the guest house, unaware of this other type of physical worship going on in the gym within the basement.

The concern with body aesthetics is rooted in Hindu beliefs. Hinduism is the world’s oldest living religion, and the third largest. In contrast to how the Western world sees the body as an extrinsic expression of our own selves to the external world, Hinduism thinks of body aesthetics as internally focused. The body is a spiritual vehicle that holistically links our world with the world of the Gods.

By keeping the body in good shape, subdued and in control, the mind is set free, and thus gains access to a higher moral order. This equilibrium is revealed through order, beauty and aesthetics.

The Mathura gym sheds light on the phenomenon of male grooming and personal care at large. In India, body aesthetics carries an extra layer of meaning. A well shaped body displays the control of the mind over body, the ultimate equilibrium of one’s own ‘temple’. Grooming is not just for others. It is, most of all, for oneself.

Yet, the country at large is still a relatively shy country for weightlifting, vs. USA and China. The owner of the gym focuses on the guest house as his ‘proper’ job, and considers the gym a local place to meet up with people who share the same passion.

India is a culture of pluralism, and at the same time, conformism. Based on their caste tradition, Indians tend to follow the path given to them, and master it. That conformism potentially opposes the individual passion for body aesthetics.

The more serious members also appreciate the current limits to the pastime. “If there was a future for bodybuilding in India, I would stay on and make it my career, but there is no real future, so I’ll go into real estate, like my father”, says another member at Keep Fit, as he prepares for his next lift.

However Indian culture is changing rapidly. The residual need for conformity is being met with higher levels of social mobility and the pursuit of less travelled, more individualistic paths. And it’s this friction between old and new, social conformity and individualistic ambition, that can be most pointedly observed within Spaces in Flux, such as the basement gym.

Mathura was the birthplace of the ‘God of Attraction’. In the future, perhaps it could also become the home of the first Indian weightlifting world champion.

Text by Natalie Gil

Photography by Anders Birger