Mechanic Stories: the green technician

In our latest edition of BAMM’s Mechanics Stories, we visited the headquarters workshop of EAV, an EV company on the forefront of developing new green alternative vehicles in city environments.

EAV’s current micro-mobility vehicles are a kind of e-cargo bike, equipped with a roof and a lithium ion battery, commonly used by other companies to quickly and securely ferry goods and parcels around busy cities.

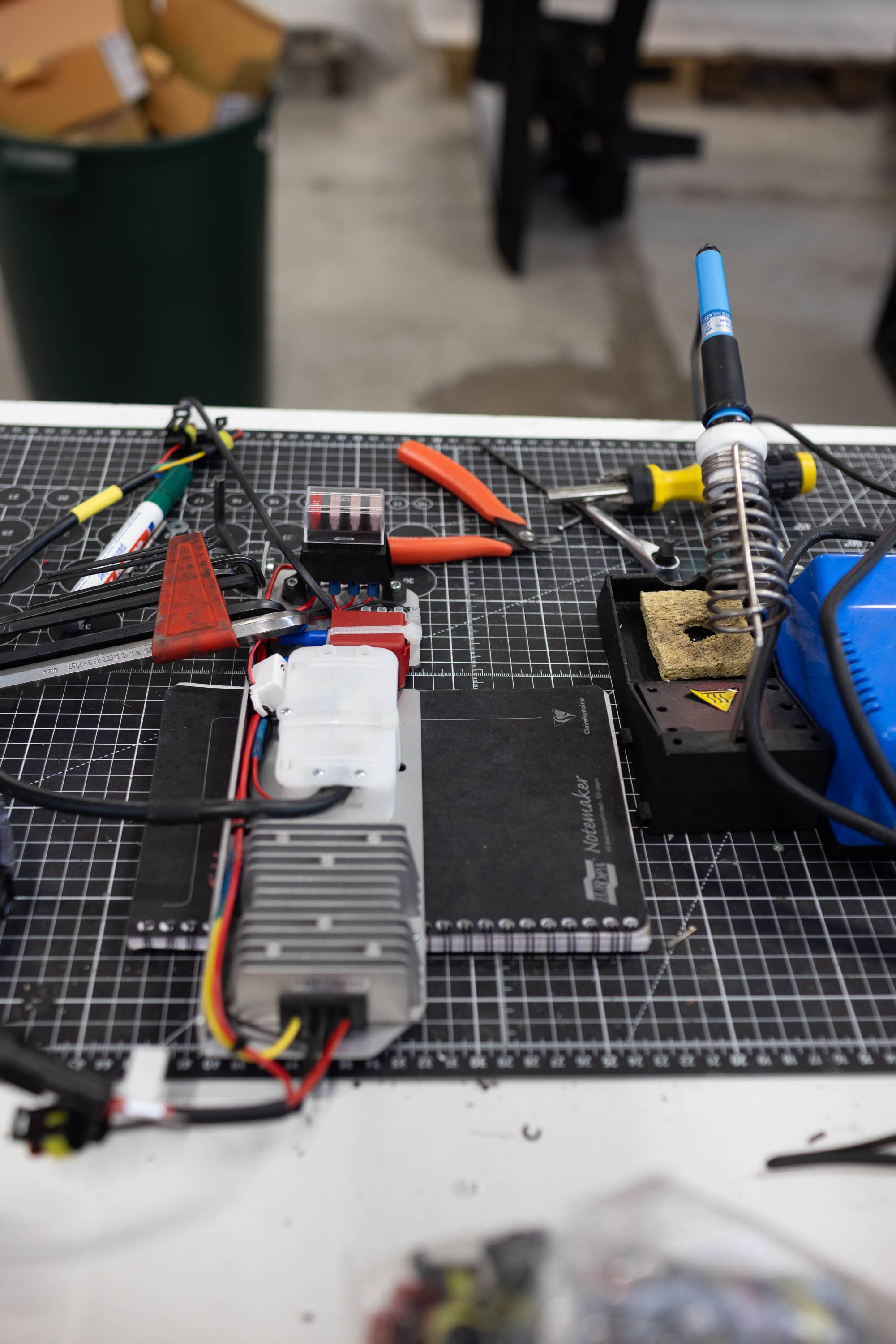

In this space the fusion of innovation and design principles is clear to see; like all of the garages we have visited in our mechanics series, there are tools and equipment all over. However there is no oil and no petrol. The air smells different, like rubber. The space is mechanical without hydrocarbons. But what drew Andy, the first technician hired by EAV, to join the world of micro mobility vehicles?

“When I got in touch with the former CEO who created this company he told me this vision, to make a better future for his kids. I was on board with that kind of ideas and kind of ended up creating that department.”

The spirit of running up the learning curve is key to the development of emerging technology (in startup terms “move fast, break things”) is evident throughout our conversation.

“I’m good at finding faults. I’ll find out what the issue is, what’s caused that, and get back down to the bare bones of it just to actually fix that issue and prevent it from happening again in the future. Then the engineers incorporate that into the new models.”

At EAV, they aim to be constantly innovative, which is reflected in Andy’s diverse professional trajectory as a weapons technician and aeronautical engineer in the RAF to maintenance technician at a £9 billion dairy site. Andy became something of a perfectionist and described himself having ‘itchy feet’, always wanting to learn about new things.

“Aeronautical engineering has a bit of a higher standard than automotive today. Yeah, I mean everything in aeronautical engineering is zero tolerance. Everything has to be perfect because if something goes wrong at 30,000 feet, no one’s going to survive it. My experience is I’ve bought into this and I’m trying to make the standards better. So every time there’s an issue, I’ll tell people to go aeronautical.”

This hybrid technician's role versus the more traditional mechanic’s role look opposite in execution: where the traditional mechanic is more static, working from a garage, this kind of technician is agile, free to go to where they are needed. For traditional mechanics, the passion for their careers is often about being the artisan of a craft, maintaining cars as they are supposed to be maintained and not about being concerned with change. However, a technician like Andy seems to be all about being multidisciplinary, not only knowing about how to fix ‘it’ but making ‘it’ better.

“In five years, we’re on our fifth cargo bike and the new one is so good. I mean, we won the international carbon bike for the year last year which was a great achievement.”

The line between mechanic and a technician is a thin one. As Andy explains: “as a maintenance engineer, you’re always being asked, ‘are you more electrical or mechanical?’ I’d say both. I've got a very good understanding of electrics, but I am more drawn towards mechanical.” And yet, he also adds that he would not fix his own car, just out of his lack if interest in the auto space.

The key comparison here is that the difference in mindset between mobility professionals exists across many areas. They agree that for now, the modern wave of innovation for vehicles is electric vehicles with lithium ion batteries, but in the future will be something different; like a hydrogen composting engine.

“I don’t think it’s going to be electric. I don’t know if electric is going to be like that in 50 years. We did a little project recently with hydrogen, so we produced some bikes which had hydrogen. There’s six of them up in Aberdeen at the moment.”

If it is certain that some customers will stick with their petrol fuel engine models, Andy rides on a new wave, adapting as fast as he can to be as sensitive to the needs of the market as possible. Comparing these trajectories to another sector, some specialists work with vintage vinyl record players while Andy is comparatively working for a music streaming startup. It shows us that regardless of the technology being levied, the human element is always key.

“So the reason engineering exists is to make life easier, to use machines to do things for us so that we don’t have to do them. But the issue is that technology isn’t perfect, sometimes it just won’t work for some reason and that reason may not be what it tells you. That’s why we will always need a human element, people to launch and control these processes.”

The label printer is Andy’s favourite ‘tool’. He shares why: “At one of my old jobs, my boss had several degrees and was a very clever man, however not very organised and kept all his nuts and bolts all in the same pot and had to dig through them just to find the right one. So with the use of a label maker I reorganised the whole store and gave everything a place so you could find it instantly. Funny enough, this didn't appeal to him. I like to have things organised and in place.”

In this fast moving landscape, the truth is that there is space for specificity when you examine context and environment. Classic auto mechanics who want to stay within their crafts are best positioned in suburban and rural settings, where traditions tend to linger for longer regardless. Yet a company like EAV, which specialises in micro mobility options for large cities and highly populated areas, focuses on the cleanest and most efficient innovations to be adopted as quickly as possible. In other words, they do different things, for different people, but each is working perfectly to serve us.

Words by: Hélène Jeunet and Victoria Landell Mills

Photography by: Hélène Jeunet